Whale shark Taroko, a beloved resident of Georgia Aquarium, has died following health complications. Discover the story behind Taroko’s life, his legacy, and what this loss means for marine conservation

Contents

- 1 The Enduring Conundrum of Captivity: A Detailed Analysis of Whale Shark Taroko’s Death at the Georgia Aquarium

- 1.1 1. A Legacy and a Loss

- 1.2 2. The Final Chapter: Taroko’s Health Decline and Euthanasia

- 1.3 3. A Chronology of Stewardship: The Georgia Aquarium’s History with Whale Sharks

- 1.4 4. The Conservation Conundrum: The Case for Captivity

- 1.5 5. The Scientific and Ethical Debate: A Critical Examination of Captivity

- 1.6 6. Public and Expert Reaction: A Community in Mourning and Debate

- 1.7 7. Conclusion: The Path Forward

The Enduring Conundrum of Captivity: A Detailed Analysis of Whale Shark Taroko’s Death at the Georgia Aquarium

The Georgia Aquarium has long been a rare cornerstone for whale shark conservation and study. In early 2025, the aquarium was featured in an episode of “Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom Protecting the Wild,” where Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant spotlighted the impressive engineering feat of housing two whale sharks—Taroko and Yushan—and emphasized the importance of observing these gentle giants in human care to advance scientific knowledge.

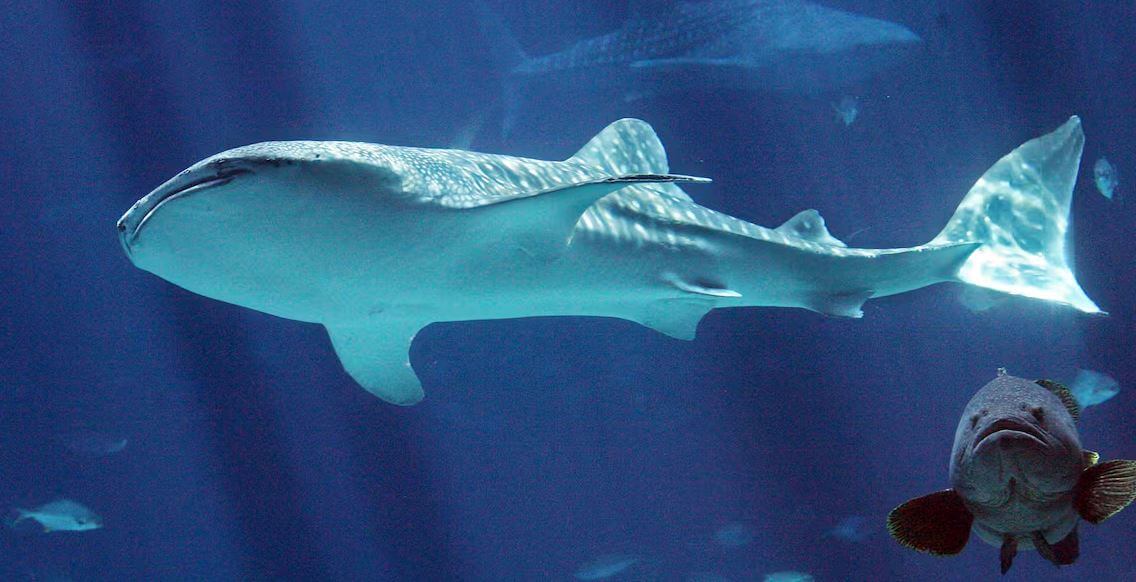

However, on August 20–21, 2025, the aquarium mourned the loss of Taroko, a male whale shark who had been with them since 2007, rescued from a Taiwanese seafood market. His declining appetite and behavior led veterinarians to humanely euthanize him. Over his nearly two-decade stay, Taroko had educated over 43 million visitors and contributed significantly to research on whale shark biology. A necropsy is planned to better understand the causes behind his health decline.

As of now, only Yushan remains in the exhibit, and the aquarium’s efforts are directed toward his welfare.

1. A Legacy and a Loss

The recent passing of Taroko, a male whale shark and a cherished resident of the Georgia Aquarium’s Ocean Voyager exhibit, marks a significant moment of reflection for the institution and the wider marine conservation community. At the core of the announcement is a profound sense of loss, tempered by the aquarium’s official statements, which frame the event as a necessary and humane decision. Taroko, who had resided at the aquarium for nearly two decades, was humanely euthanized after a prolonged health decline. The aquarium, a premier facility and the only one in the Western Hemisphere to display this species, described the undertaking of caring for whale sharks as an “immense honor” and noted that Taroko’s presence had contributed significantly to a deeper understanding of whale shark biology, health, and behavior.

This event is not merely an isolated incident of an animal’s death in a zoological setting; it is a pivotal moment that brings to the forefront a decades-old debate about the ethics of keeping migratory megafauna in confinement. Taroko was originally rescued from a seafood market in Taiwan in 2007, a circumstance that has long served as a central justification for his captivity and that of his fellow whale sharks at the institution. While his life in captivity served as a powerful educational tool, seen by more than 43 million visitors , his death reignites persistent questions about whether any man-made environment can truly sustain these colossal creatures, or whether the benefits of display and research can ever outweigh the inherent biological challenges of confinement. This report provides a detailed examination of the circumstances surrounding Taroko’s death, placing it within the historical context of the Georgia Aquarium’s whale shark program and analyzing the broader scientific and ethical tensions that continue to define the conversation.

2. The Final Chapter: Taroko’s Health Decline and Euthanasia

The final days of Taroko’s life were marked by a discernible and irreversible decline in his overall condition. According to official announcements, veterinary staff and animal care teams noticed changes in his appetite and behavior during their routine wellness monitoring. This change in condition prompted a series of veterinary interventions and intensive care efforts, which were ultimately unable to reverse the animal’s downward trajectory. Faced with a deteriorating state that could not be improved, the aquarium made the “humane decision to euthanize” the whale shark. The institution’s public statements reflect a deep emotional toll on the staff, with one spokesperson noting that the grief felt was as profound as losing a cherished pet.

In the wake of his passing, the Georgia Aquarium confirmed that a necropsy, or animal autopsy, would be conducted. The stated purpose of this procedure is to gain comprehensive insights into the specific health issues that precipitated his decline, with the ultimate goal of contributing to the scientific understanding of the species. This focus on the necropsy as a scientific opportunity is a consistent institutional position. It serves to reposition the animal’s death from a simple tragedy to a valuable learning moment that can benefit the entire species. The institution’s narrative has long framed the lives and deaths of their whale sharks as a “gift that keeps on giving” to science and conservation, where even in death, the animals’ presence serves the higher purpose of advancing knowledge about a species that remains largely a mystery in the wild. This approach provides a strategic counterpoint to critics who view the deaths as a fundamental failure of the captive environment. By emphasizing the scientific and educational contributions, the aquarium reframes the narrative as a necessary, if painful, component of its broader conservation mission.

3. A Chronology of Stewardship: The Georgia Aquarium’s History with Whale Sharks

Taroko’s death is the latest chapter in a long history of the Georgia Aquarium’s program for its iconic whale shark residents. The program began with the arrival of the first four whale sharks—Ralph, Norton, Alice, and Trixie—in 2005 and 2006. A central narrative, consistently presented by the aquarium, is that these animals were “rescued” from being sold for human consumption in Taiwan, a fate that would have been certain had the institution not intervened.

However, the program has been marked by recurring challenges and fatalities. The first significant public controversy arose in 2007 with the deaths of Ralph and Norton. Ralph died on January 11, with a necropsy from the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine attributing his death to stomach problems that caused peritonitis, an inflammation of the abdominal membrane. Aquarium officials theorized that his declining appetite was linked to a chemical used to treat a parasitic leech in the exhibit, though the necropsy was inconclusive on this point. Norton’s death followed just a few months later in June, after a similar health decline and loss of appetite that coincided with the use of the same pesticide. These early deaths led to significant public backlash and criticism from animal rights activists.

The pattern continued over a decade later. Trixie, the largest female, passed away in November 2020 after her health declined and she experienced difficulty navigating her habitat. Less than a year later, in 2021, Alice was also euthanized after her behavior and bloodwork showed a decline. Both of these later deaths were attributed to a general “health decline” rather than a specific, identifiable environmental factor. The death of Taroko in 2025, also following a generalized decline, fits this more recent pattern.

The history of the Georgia Aquarium’s whale shark program, as evidenced by the mortality data, illustrates an evolution in the challenges faced by the institution. While the deaths of Ralph and Norton could be linked, even if inconclusively, to a specific husbandry issue (the parasitic treatment), the later deaths of Trixie, Alice, and now Taroko were attributed to more ambiguous, generalized health deterioration. This pattern suggests that while the aquarium may have successfully resolved initial husbandry problems, the long-term biological toll of captivity on a species with a century-plus lifespan remains a persistent and unresolved issue. The succession of these deaths, each with its own set of circumstances, reinforces the central idea that maintaining the health of these enormous animals in a man-made environment is a monumental and perhaps fundamentally flawed undertaking.

4. The Conservation Conundrum: The Case for Captivity

For decades, the Georgia Aquarium has maintained a powerful and multi-faceted argument in favor of its whale shark program, positioning itself not merely as a tourist attraction but as a vital hub for conservation, education, and research. At the heart of this justification is the “rescue” narrative. The aquarium asserts that its whale sharks were procured from a Taiwanese fishing quota, where they would have otherwise been killed for human consumption, a practice now banned. This ethical foundation frames the institution as a life-saver and the only viable alternative to certain death.

Beyond this foundational narrative, the aquarium points to its substantial contributions to scientific knowledge. Through collaborations with leading universities such as Georgia State University, Emory University, and the Georgia Institute of Technology, the institution has compiled an unprecedented body of data on the species. This includes the use of cutting-edge analytical techniques to explore the chemistry of their blood, and a DNA study that led to the first complete genome map of a shark. The aquarium’s research extends far beyond its tanks, with extensive

in situ (in the wild) field research, including the world’s largest satellite tagging program for whale sharks in Mexico, and expeditions to St. Helena and the Galapagos Islands.

Recent formal partnerships with preeminent Japanese and Taiwanese research institutions further solidify this standing. These collaborations aim to pool resources and expertise to advance conservation strategies for whale sharks and other threatened marine species, providing the aquarium with a platform to share its knowledge on an international scale. The final pillar of the aquarium’s argument rests on public education. By providing direct, in-person access to these magnificent creatures, the institution believes it inspires a shared sense of responsibility for conserving aquatic ecosystems in a way that is difficult to replicate through other mediums. The institution’s strategy is to establish its status as a leading scientific institution, not just a public exhibit. By highlighting collaborations with major universities and international partners, they build a formidable defense against critics, elevating their mission beyond entertainment to a complex and necessary component of global conservation.

5. The Scientific and Ethical Debate: A Critical Examination of Captivity

The death of Taroko, despite the Georgia Aquarium’s extensive conservation efforts, brings to the forefront the core scientific and ethical arguments against the confinement of whale sharks. A fundamental point of contention is the sheer scale and biological needs of the species. Whale sharks are naturally migratory, inhabiting vast, open ocean environments, and are rarely found in waters below 21°C. Scientific studies estimate their lifespan in the wild to be between 80 and 130 years. The Georgia Aquarium’s 6.3 million US gallons (24,000 m³) Ocean Voyager exhibit, while one of the largest in the world, represents a fraction of the open ocean these creatures traverse. This contrast highlights the fundamental incompatibility between a whale shark’s biology and a confined tank, regardless of its size.

Perhaps the most compelling argument against captivity is found in mortality data. A Japanese study noted that whale sharks in captivity survive on average for less than two years. When data from aquarium whale sharks were included in a scientific study on their growth, it significantly reduced the estimated average asymptotic size of females, suggesting a potential stunting effect of captivity. Taroko’s remarkable 18-year tenure, therefore, stands out as a significant exception to a generally poor record, rather than a normative example of captive longevity. This single fact pattern elevates the debate from philosophical to empirical, illustrating that while the Georgia Aquarium can claim to be a “gold standard” , even a successful example within a fundamentally flawed system is still subject to its limitations.

Critics also point to the potential for behavioral and physiological stress. Observations of repetitive circling behavior are often noted by visitors, drawing parallels to similar behaviors observed in large mammals in zoos. While some sources debate whether fish can experience the kind of depression seen in mammals, the idea of a creature swimming in circles for years in a confined space is a powerful image for those who argue against captivity. The challenges of confining large, mobile creatures are further illuminated by examining studies on captive killer whales, which note a high rate of stress-related illnesses and mortality factors like infections and hemorrhages. While whale sharks are not marine mammals, the parallels are relevant to the broader challenges of maintaining species that are not biologically suited for confinement. Finally, the counter-argument to the “rescue” narrative suggests that the claim of certain death in Taiwan is not a universally accepted fact and that some animals simply should not be kept in captivity at all, regardless of the circumstances of their initial acquisition. The debate is no longer simply about the ethics but about whether it is possible to replicate the natural environment for such a creature, even with the best intentions and technology.

6. Public and Expert Reaction: A Community in Mourning and Debate

The announcement of Taroko’s death was met with a swift and multifaceted reaction across public and online forums. Social media platforms like Reddit and TikTok were flooded with a blend of genuine sadness, personal memories, and philosophical reflection. Visitors shared stories of their emotional connections to the whale shark, recalling the sense of awe and wonder they felt seeing him for the first time. This outpouring of grief from millions who saw him over the years underscores the aquarium’s success in its educational mission. However, alongside the mourning, a strong undercurrent of moral outrage was also evident, with many users questioning the very practice of keeping such a large, migratory creature in confinement. The discourse ranged from simple statements like “Whale sharks don’t belong in tanks” to more complex arguments about depression and the lack of natural behavior in captivity.

A notable aspect of the reaction was the conspicuous absence of a new, formal statement from major animal welfare organizations like PETA or the Humane Society specifically on Taroko’s death. While these organizations have a long-standing position against the confinement of large marine animals, their historical criticisms, which are often cited in older articles and forum comments, were used to frame the debate rather than a new condemnation. This observation is itself significant. It suggests that the Georgia Aquarium’s established reputation as a leading research institution, combined with its transparency regarding the health and mortality of its animals, may have preempted a strong, immediate condemnation. The debate has largely shifted from a one-sided protest to a more nuanced, community-level discussion playing out on social media, indicating an evolution in the public discourse surrounding animal captivity.

7. Conclusion: The Path Forward

The death of Taroko, after nearly two decades of life at the Georgia Aquarium, serves as a poignant reminder of the complex and often conflicting goals of modern zoological institutions. His life was a testament to the advancements in animal husbandry and a beacon for the public’s enduring fascination with these gentle giants. The dedicated, world-class care provided by the aquarium and its significant research contributions stand in stark contrast to the inherent biological and ethical challenges of confining a migratory species with an over-century lifespan.

Looking ahead, the path forward for institutions that care for such species must be multi-pronged. It should involve a continued focus on robust, in situ (field) research as a primary mission, leveraging the aquarium’s resources and expertise to better understand and protect wild populations. Furthermore, the conversation must expand to include the increasing use of technology, such as virtual reality, augmented reality, and animatronics, to create immersive and educational experiences without the need for live animal confinement, a solution advocated by some critics. The aquarium can also maintain its commitment to radical transparency, openly sharing information about animal health, morbidity, and mortality to build trust and foster informed public dialogue.

Taroko’s legacy is twofold: he was an ambassador who brought millions of people face-to-face with the majesty of his species, inspiring a generation of conservationists. His death, however, serves as an equally powerful, if somber, lesson. It is a reminder that while humans can learn and adapt to provide for these magnificent creatures, the ultimate question of whether they truly belong in our care remains a critical and unresolved part of the conservation narrative.