Contents

- 1 The Rise of “Frankenstein Rabbits” in Colorado: What’s Really Happening Behind Those Horns and Tentacles?

- 2 A Closer Look: What Locals Are Seeing

- 3 The Culprit: Shope Papilloma Virus

- 4 A Virus With a Strange History

- 5 How Dangerous Is SPV to Rabbits?

- 6 Is It Dangerous to Humans or Pets?

- 7 What To Do If You Spot a “Frankenstein Rabbit”

- 8 Why This Summer? Why Now?

- 9 The Internet Reacts: From Horror to Humor

- 10 The Folklore Connection: Jackalopes and Beyond

- 11 Lessons From the “Frankenstein Rabbit” Phenomenon

The Rise of “Frankenstein Rabbits” in Colorado: What’s Really Happening Behind Those Horns and Tentacles?

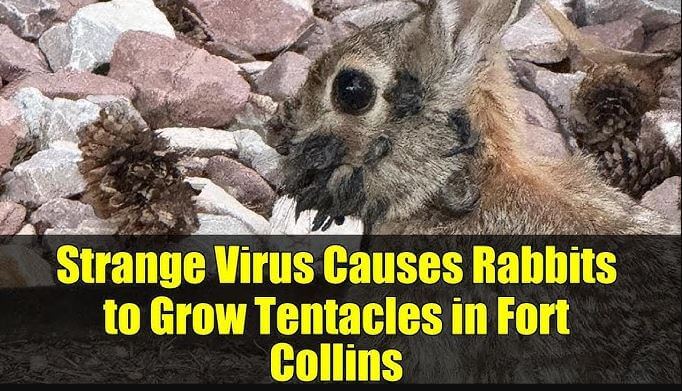

It sounds like something straight out of a low-budget horror movie — wild rabbits roaming the Colorado plains, sprouting black, horn-like protrusions and sinister, tentacle-shaped growths across their faces. Some locals have dubbed them “Frankenstein rabbits,” a nickname that spreads almost as quickly as the shock when you first see one.

But this is no work of science fiction. It’s a very real, very odd phenomenon — and it’s making many residents in northern Colorado do a double-take this summer.

Eyewitness accounts describe rabbits with “black quills” jutting out from their heads, “toothpick-like” spikes surrounding their eyes, or dark, scabby masses that look almost alien in nature. The unsettling appearance has prompted questions: Is this some kind of new mutant species? A sign of environmental disaster? Or could it be the result of something far more ordinary — yet still bizarre — from the natural world?

The answer, as it turns out, lies at the intersection of wildlife biology, insect activity, and an almost century-old virus with a strangely fascinating history.

Rabbits with Tentacles: A Deep Dive into the Internet’s Wildest Theory

A Closer Look: What Locals Are Seeing

Residents of Fort Collins and other parts of northern Colorado have been spotting the unusual animals for weeks. The sightings tend to happen in grassy fields, backyards, or even along suburban sidewalks — places where wild cottontail rabbits normally graze without drawing much attention.

Only this time, the rabbits are impossible to ignore.

From a distance, they might look like they’ve tangled with a cactus and lost, the dark spikes resembling clumps of thorns lodged in their fur. But a closer glance reveals that these growths are actually part of their bodies, sprouting from skin along the head, face, and occasionally the neck.

Some growths are short and stubby; others are elongated, curling outward like twisted antlers. And while the rabbits themselves often appear to be behaving normally — hopping, foraging, grooming — the sight is enough to make passersby freeze in place.

The Culprit: Shope Papilloma Virus

The black, tentacle-like growths are not tumors from industrial pollution or radiation leaks, as some wild theories suggest. Instead, wildlife experts say they’re most likely the work of Shope papilloma virus (SPV) — a disease that has been quietly affecting rabbit populations for decades.

SPV is a virus that specifically targets rabbits, producing wart-like, waxy growths on the skin, most commonly around the head and face. In the simplest terms, these growths are skin tumors — but they are benign in most cases, meaning they don’t spread internally or cause significant pain.

The virus spreads through biting insects such as fleas, mosquitoes, and ticks, which act as tiny, unknowing couriers. In the summer months, when insect populations explode and rabbit densities increase, SPV cases tend to rise as well. This is why wildlife agencies in states like Colorado, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Texas see more cases during warmer seasons.

“It’s something we see periodically, and it tends to look a lot worse than it actually is for the animal,”

explains Kara Van Hoose, spokesperson for Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW).

“The rabbits can still go about their normal lives unless the growths interfere with feeding or movement.”

A Virus With a Strange History

While the sight of these horned rabbits is enough to shock even seasoned hikers, the virus itself has a rather fascinating history — one that once blurred the lines between wildlife biology and early cancer research.

SPV was first described in the 1930s by Dr. Richard E. Shope, an American virologist who noticed wild cottontails in Iowa developing horn-like protrusions. His work revealed that the growths were caused by a virus, not a genetic mutation. This was groundbreaking because it offered one of the first clear examples of a virus inducing cancer-like tumors in animals.

Shope’s discovery became a stepping stone for future cancer research, helping scientists understand how certain viruses could trigger abnormal cell growth in mammals. In other words, those creepy rabbit “horns” indirectly helped advance medical science.

How Dangerous Is SPV to Rabbits?

For the most part, SPV is a cosmetic — albeit dramatic — condition. The growths can vary in size from small, rough patches to elongated spikes that resemble miniature antlers.

In mild cases, rabbits live normal lives with these growths for months. In severe cases, however, the growths can become so large that they block vision, interfere with chewing, or make it difficult to drink. That’s when the virus crosses from harmless oddity into a real threat to the animal’s survival.

Julie Lindstrom, a supervisor at Sioux Falls Police Animal Control in South Dakota, notes that there is no rehabilitation method for wild rabbits infected with SPV. Euthanasia is generally not recommended unless the animal is clearly suffering or unable to eat.

Is It Dangerous to Humans or Pets?

Here’s the good news: SPV cannot infect humans, dogs, cats, or other non-rabbit animals. The virus is highly species-specific, meaning only rabbits are susceptible.

That said, CPW advises that people — and their pets — should keep a respectful distance from any infected rabbits they encounter. Not only is it best for the rabbit’s own safety (stress can harm wild animals), but it also reduces the chance of pets picking up fleas or ticks that might carry other diseases.

Domestic rabbits that live outdoors could, in theory, contract SPV if bitten by infected insects or if they come into contact with wild rabbits. Indoor rabbits, on the other hand, face virtually no risk.

What To Do If You Spot a “Frankenstein Rabbit”

The sight might tempt you to call animal control, but in most cases, that’s unnecessary. Unless the rabbit appears injured or severely hindered by the growths, wildlife agencies prefer to let nature take its course.

If you do see a rabbit struggling to move, eat, or drink, you can contact your local animal control office or wildlife rehabilitation center for guidance.

And if you happen to find a dead rabbit on your property — infected or not — Lindstrom says it’s safe to handle it yourself as long as you wear gloves and practice good hygiene afterward.

Why This Summer? Why Now?

Several factors may be combining to make SPV more noticeable in Colorado this year:

-

Warmer Weather and Longer Summers – Climate shifts may be extending insect activity periods, giving the virus more opportunity to spread.

-

Higher Rabbit Populations – Cottontail numbers tend to fluctuate year by year; a population boom means more hosts for the virus.

-

Public Awareness – With more people spending time outdoors post-pandemic, unusual wildlife sightings are more likely to be noticed and shared online.

-

Social Media Amplification – A single photo of a horned rabbit can go viral (pun intended), making the phenomenon seem more widespread than it truly is.

The Internet Reacts: From Horror to Humor

When photos of horned rabbits first started making the rounds on local Facebook groups and Twitter feeds, reactions ranged from concerned to downright comical.

Some joked about “Jackalopes finally coming to life” — referencing the mythical antlered rabbit of American folklore. Others made comparisons to science experiments gone wrong or video game monsters.

Of course, alongside the jokes came genuine fear that this was the sign of a dangerous new disease or environmental crisis. That’s why wildlife experts are quick to stress that SPV is neither new nor dangerous to humans.

The Folklore Connection: Jackalopes and Beyond

Interestingly, some historians believe that real-life SPV-infected rabbits may have helped inspire the legend of the jackalope — a mythical creature depicted as a rabbit with antelope horns. First popularized in Wyoming in the 1930s, the jackalope became a quirky part of American roadside culture, with souvenir shops selling mounted “jackalope heads” and postcards.

While taxidermists often faked these creatures using deer antlers, it’s entirely possible that early settlers or hunters had, in fact, seen SPV-infected rabbits and spun tall tales around them.

Lessons From the “Frankenstein Rabbit” Phenomenon

While the sight is unsettling, the story of SPV is ultimately one about the strange and resilient ways nature adapts. Viruses like SPV have existed for generations, coexisting with their hosts in a delicate balance.

For humans, the phenomenon is a reminder that nature is full of surprises — some beautiful, some eerie, but all worth understanding. It’s also a testament to the value of scientific investigation, which can turn a scene straight out of a horror movie into a fascinating piece of ecological history.

So the next time you see a rabbit with black horns or tentacles on its face, take a moment to appreciate that you’re witnessing one of nature’s stranger designs. Just keep your distance, snap a photo if you must, and let the wild world continue its strange and mysterious dance.

Bottom line: The “Frankenstein rabbits” of Colorado aren’t mutants, harbingers of doom, or the result of shadowy government experiments. They’re simply victims of an old, species-specific virus spread by summer insects — a virus that, for all its unsettling effects, has played a surprising role in scientific discovery.

And like many things in nature, they remind us that the line between the ordinary and the extraordinary is often far thinner than it seems.